Finance

What Is Fair Value In Accounting

Published: October 13, 2023

Learn the role of fair value in accounting and its impact on financial reporting. Gain a deeper understanding of finance concepts and principles.

(Many of the links in this article redirect to a specific reviewed product. Your purchase of these products through affiliate links helps to generate commission for LiveWell, at no extra cost. Learn more)

Table of Contents

Introduction

When it comes to accounting, one term that frequently comes up is “fair value.” But what exactly does fair value mean in accounting? Fair value is a fundamental concept that plays a crucial role in financial reporting and measurement. It helps provide a realistic and unbiased assessment of the value of assets, liabilities, and financial instruments.

Fair value accounting is based on the principle that financial statements should reflect the true value of an entity’s assets and liabilities as of the reporting date. It aims to provide users of financial statements, such as investors, lenders, and regulators, with reliable and transparent information about an entity’s financial position.

Historically, accounting standards used historical cost-based measurements, where assets and liabilities were recorded at their original purchase price. However, this method had limitations, particularly in capturing the current market values of assets and liabilities.

In response to these limitations, fair value accounting emerged as an alternative approach. It recognizes that the value of assets and liabilities can change over time due to market fluctuations, changes in demand and supply, and other relevant factors. Fair value provides a more accurate representation of an entity’s financial condition by reflecting the current market conditions.

Fair value is not a fixed concept but rather a measure that can vary depending on the specific circumstances and context. It involves the use of various measurement techniques and assumes an orderly transaction between market participants.

Next, we’ll delve into the definition of fair value and explore its historical context to gain a deeper understanding of its significance in accounting.

Definition of Fair Value

In accounting, fair value refers to the estimated price at which an asset or liability would be exchanged between knowledgeable and willing parties in an arm’s length transaction. It represents the current market value of an asset or liability, based on the assumptions that market participants would make.

The fair value measurement takes into account both observable market prices and estimates when market prices are not readily available. It considers factors such as supply and demand, market liquidity, and the perceived risk associated with the asset or liability.

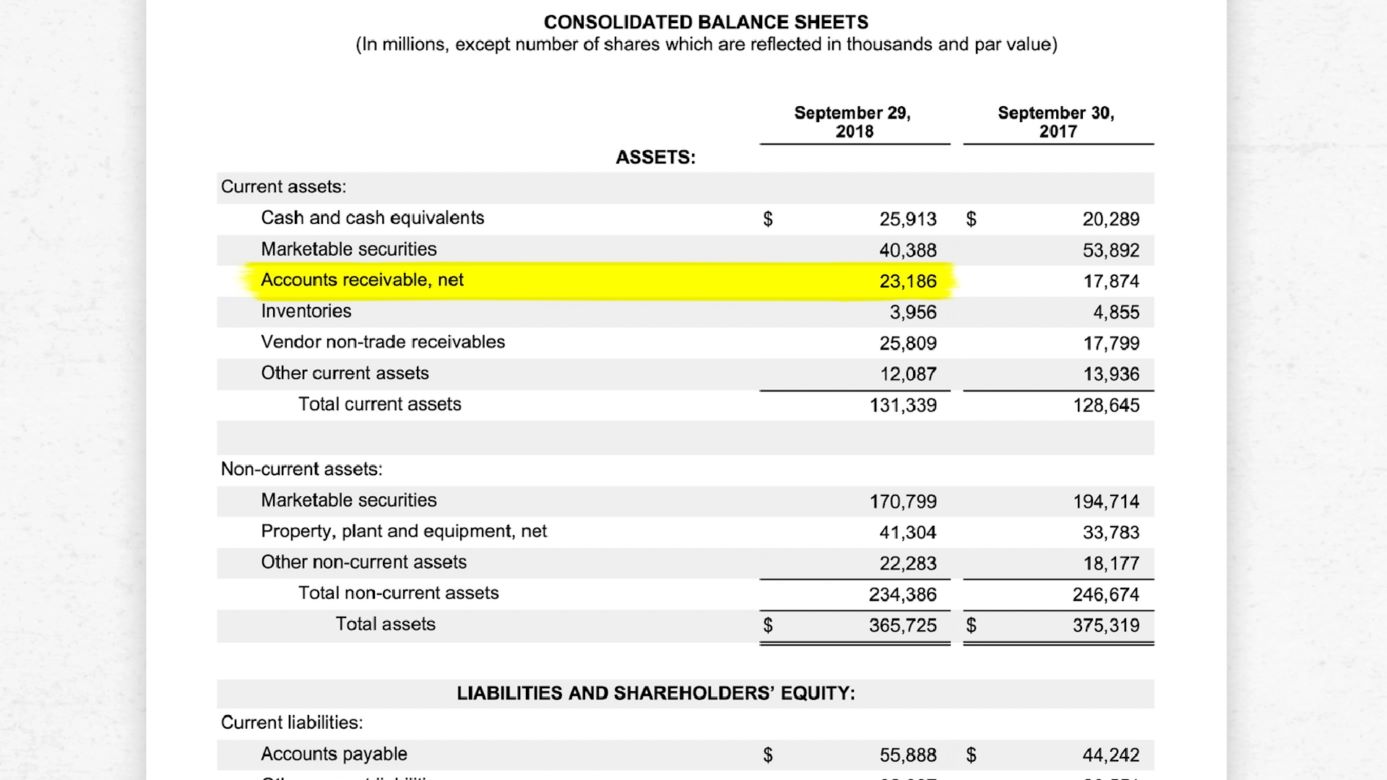

Fair value is not just limited to tangible assets like property, plant, and equipment. It also encompasses financial instruments, such as stocks, bonds, derivatives, and other securities. Additionally, it applies to intangible assets like patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

As an accounting principle, fair value aims to provide users of financial statements with relevant and reliable information about an entity’s assets and liabilities. It ensures that financial statements are not only based on historical cost but also on the current market conditions.

Fair value measurements are conducted using various techniques, which we will discuss in the next section. These techniques may include market-based approaches, income-based approaches, and cost-based approaches. The choice of technique depends on the nature of the asset or liability being valued and the availability of relevant data.

It’s important to note that fair value is not an arbitrary value assigned by an accountant or financial professional. It is a result of a systematic and rigorous process that adheres to accounting standards and principles, such as the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

Now that we have a clear understanding of the definition of fair value, let’s explore its historical context and how it has evolved over time.

Historical Context

The concept of fair value in accounting has its roots in the late 20th century when there was a growing recognition of the limitations of historical cost accounting. Historical cost accounting was the prevailing method for valuing assets and liabilities, where items were recorded at their original purchase price.

However, as the global economy became more complex and dynamic, it became clear that historical cost accounting did not adequately reflect the true economic value of assets and liabilities. As a result, there was a need for a more accurate and relevant measurement basis.

This need led to the development and adoption of fair value accounting, which gained traction in the 1990s. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) recognized the importance of fair value in providing users of financial statements with more timely and relevant information.

The adoption of fair value accounting was further accelerated by events such as the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s and the global financial crisis of 2008. These events highlighted the shortcomings of historical cost accounting in capturing the rapid changes in asset values and the inherent risks associated with financial instruments.

The shift towards fair value accounting was also driven by the increasing complexity and diversity of financial instruments and derivatives. These instruments often have fluctuating market values and require a more dynamic approach to measurement.

However, the implementation of fair value accounting has not been without controversy. Critics argue that fair value can be subjective and prone to manipulation, especially during times of market volatility. They argue that it can create excessive volatility in financial statements and may not accurately capture the long-term value of assets and liabilities.

Despite the criticisms, fair value accounting has continued to be a dominant measurement basis in accounting standards, with ongoing refinements to enhance its transparency and reliability. The aim is to strike a balance between capturing the current market value of assets and liabilities while providing users of financial statements with useful and reliable information.

Now that we understand the historical context of fair value accounting, let’s explore the techniques used to measure fair value.

Fair Value Measurement Techniques

There are various techniques used to measure fair value, depending on the nature of the asset or liability being valued and the availability of relevant market data. These techniques aim to provide an objective and reliable estimate of the current market value.

1. Market Approach: This approach relies on market-based inputs and uses the prices of comparable assets or liabilities that are actively traded in the market. It may involve using market multiples, comparable sales, or quoted prices to determine the fair value. The market approach is particularly useful when there is an active market for similar assets or liabilities.

2. Income Approach: The income approach estimates fair value by discounting the future cash flows expected to be generated by the asset or liability. This technique takes into consideration the time value of money and the risk associated with the cash flows. It is commonly used for valuing income-generating assets, such as real estate properties or financial instruments.

3. Cost Approach: The cost approach involves estimating fair value based on the cost of acquiring or constructing a similar asset. It considers the current replacement cost, adjusted for depreciation or obsolescence. This technique is often used for valuing assets with no active market or when market-based or income-based approaches are not applicable.

It’s important to note that fair value measurements may not solely rely on one technique but may involve a combination of approaches. The choice of technique depends on the availability and relevance of data, the characteristics of the asset or liability, and the specific accounting standards or regulations being followed.

Fair value measurements are influenced by various factors, such as market liquidity, supply and demand dynamics, and the level of risk associated with the asset or liability. While the techniques used provide a reasonable estimate of fair value, it’s important to recognize that fair value is inherently subjective to some degree.

To ensure consistency and comparability, accounting standards provide guidance on how fair value measurements should be applied, including the use of valuation techniques, determination of inputs, and disclosures required in financial statements.

Now that we have understood the different measurement techniques, let’s explore the fair value hierarchy used to categorize the inputs used in the fair value measurement process.

Fair Value Hierarchy

The fair value hierarchy is a classification system used to categorize the inputs used in fair value measurements. It provides guidance on the reliability and level of observability of the inputs, giving users of financial statements a better understanding of the basis for fair value measurements.

The hierarchy consists of three levels that rank the inputs based on their reliability and availability:

Level 1: Quoted Prices in Active Markets

The highest level of the hierarchy includes inputs that are based on quoted prices in active markets for identical assets or liabilities. These inputs are the most reliable and observable, as they reflect actual market transactions where buyers and sellers interact. Examples of level 1 inputs include listed stocks on a stock exchange or exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

Level 2: Observable Inputs

The second level consists of inputs that are based on observable market data other than quoted prices in active markets. This may include quoted prices for similar assets or liabilities, benchmark yields, interest rates, or other market indicators. These inputs are derived from market data, but they may require some level of adjustment or estimation. Level 2 inputs provide a reasonable degree of reliability, although they are not as directly observable as level 1 inputs.

Level 3: Unobservable Inputs

The lowest level of the hierarchy includes inputs that are unobservable in the market or have little or no corroborating market data. These inputs rely on management’s estimates and assumptions, and they may involve complex models or techniques. Level 3 inputs are typically used when no active market exists or when significant judgment is required to determine the fair value. Examples of level 3 inputs include valuations based on discounted cash flow models or appraisals of unique properties.

The hierarchy’s purpose is to promote consistency and comparability in fair value measurements. It helps users understand the reliability and limitations of the inputs used, allowing them to assess the quality of the fair value estimates provided in financial statements.

Financial reporting standards require entities to disclose the level of inputs used in fair value measurements and provide additional information about the inputs, valuation techniques, and significant assumptions applied. This transparency helps users make informed decisions and evaluate the sensitivity of fair value measurements to changes in the underlying assumptions.

Now that we understand the fair value hierarchy, let’s explore the role of fair value in financial reporting.

Role of Fair Value in Financial Reporting

Fair value plays a crucial role in financial reporting by providing users of financial statements with relevant and reliable information about an entity’s financial position. It enhances the transparency and accuracy of financial statements by reflecting the current market value of assets, liabilities, and financial instruments.

Here are some key roles and benefits of fair value in financial reporting:

1. Enhanced Relevance: Fair value accounting provides users with more timely and relevant information about an entity’s assets and liabilities. It reflects the current market conditions and helps stakeholders make informed decisions by providing a clearer picture of an entity’s financial position.

2. Reflects Economic Reality: Fair value accounting recognizes that the value of assets and liabilities can change over time due to market fluctuations and other relevant factors. It aligns financial statements with the economic realities of an entity’s assets and liabilities, providing a more accurate representation of its financial condition.

3. Transparency and Comparability: Fair value measurements are based on defined standards and guidelines, promoting transparency and comparability across different entities and industries. This allows users to assess and compare the fair value measurements of different entities, enabling better evaluation and analysis.

4. Proper Risk Assessment: Fair value accounting captures the inherent risks associated with financial instruments and other assets or liabilities. By valuing these items at their fair values, it enables users to assess the potential risks and exposures faced by the entity and make more informed risk management decisions.

5. Improved Decision-Making: By providing more accurate and relevant information, fair value accounting assists investors, lenders, and other stakeholders in making more informed decisions. Whether it’s evaluating investment opportunities, assessing creditworthiness, or analyzing an entity’s overall financial health, fair value measurements contribute to better decision-making processes.

6. Increased Accountability: Fair value accounting holds entities accountable for the true value of their assets and liabilities. It discourages practices of inflating or understating values or hiding potential risks, promoting greater accountability and transparency in financial reporting.

While fair value accounting offers numerous benefits, it is not without its challenges and criticisms, which we will discuss in the next section. Nonetheless, fair value remains a critical component of financial reporting, providing users with valuable insights into an entity’s financial standing.

Now that we understand the role of fair value in financial reporting, let’s explore some of the challenges and criticisms associated with fair value accounting.

Challenges and Criticisms of Fair Value Accounting

While fair value accounting offers significant benefits in enhancing the transparency and relevancy of financial reporting, it is not without its challenges and criticisms. Critics argue that fair value accounting can be subjective, volatile, and may not always accurately represent the long-term value of assets and liabilities.

Here are some of the key challenges and criticisms of fair value accounting:

1. Subjectivity and Inherent Judgment: Fair value measurements often require the use of management estimates, assumptions, and models, especially for level 2 and level 3 inputs. This subjectivity can lead to variations in fair value estimates between different entities and even within the same entity over time. Critics argue that the reliance on management judgment makes fair value susceptible to manipulation or bias.

2. Increased Volatility: Fair value accounting can result in increased volatility in financial statements, especially during periods of market uncertainty or economic downturns. This volatility can make it challenging for users of financial statements to assess the true underlying performance and financial health of an entity. Critics argue that this increased volatility can lead to short-term decision-making and hinder long-term investment strategies.

3. Lack of Active Markets and Reliable Data: Fair value measurements rely heavily on the availability of observable market data, especially for level 1 inputs. However, not all assets and liabilities have active markets, especially for those with unique or illiquid characteristics. In such cases, fair value measurements may rely on less reliable or unobservable inputs, increasing the uncertainty and potential for errors in the valuation process.

4. Complexity and Cost of Valuation: Fair value accounting often requires complex valuation models, especially for level 2 and level 3 inputs. These models may involve sophisticated financial techniques and expertise, which can be costly and time-consuming to implement. Critics argue that the complexity of fair value measurements may outweigh the benefits, especially for smaller entities with limited resources.

5. Difficulty in Assessing Long-Term Value: Fair value measurements are often based on short-term market prices and expectations, which may not accurately reflect the long-term value of certain assets or liabilities. Critics argue that fair value accounting may not capture the intrinsic value of assets that generate long-term benefits or have strategic importance to an entity. This can be particularly relevant for assets such as intellectual property or research and development projects.

Despite these challenges and criticisms, fair value accounting continues to be widely adopted and accepted as a valuable measurement basis for financial reporting. Efforts are continuously being made to address these concerns and improve the transparency, reliability, and comparability of fair value measurements.

Now, let’s explore some examples of fair value measurements in practice to deepen our understanding of how it is applied in different scenarios.

Examples of Fair Value Measurements

Fair value measurements are used across various asset classes and financial instruments. Here are some examples of how fair value is applied in practice:

1. Stocks and Bonds: Fair value is commonly used to determine the value of publicly traded stocks and bonds. The quoted market prices for these instruments in active markets are typically considered level 1 inputs. However, if market prices are not readily available, fair value can be estimated using similar instruments or valuation models based on market and economic data.

2. Derivatives: Fair value is crucial for valuing derivatives, such as options, futures contracts, and swaps. These complex financial instruments derive their value from an underlying asset or underlying market factors. Fair value measurement techniques, such as the Black-Scholes model for options, are used to estimate the fair value of derivatives based on observable market inputs and assumptions.

3. Real Estate: Fair value is used in the valuation of real estate properties, including commercial buildings, residential properties, and land. The market approach is often applied, considering recent sales of comparable properties in the market. If there are no readily available market prices, fair value can be estimated using the income approach by discounting future cash flows generated by the property.

4. Intangible Assets: Fair value plays a role in valuing intangible assets, such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights. Estimating the fair value of these assets can be challenging as there may not be active markets or comparable transactions. Valuation techniques, such as the income approach or cost approach, are applied to estimate the fair value based on projected future cash flows or replacement costs.

5. Private Equity Investments: Fair value is used to determine the value of private equity investments, which are often not publicly traded. Valuation techniques, such as the income approach or market approach, are employed to estimate the fair value of these investments based on factors such as the performance of the underlying business, comparable companies, or recent transactions in the industry.

6. Financial Liabilities: Fair value is relevant for measuring financial liabilities, such as bonds, loans, and convertible instruments. The fair value of these liabilities is determined based on market interest rates, credit risk, and other factors that impact their value. Changes in fair value may result in gains or losses being recognized in financial statements.

These examples highlight the wide range of assets and liabilities where fair value measurements are applied. The specific valuation techniques and inputs used may vary depending on the characteristics of the asset or liability and the available market data.

Now, let’s conclude our discussion on fair value accounting.

Conclusion

Fair value accounting is a fundamental concept in finance and accounting that helps provide a realistic and unbiased assessment of the value of assets, liabilities, and financial instruments. It enhances the transparency and relevance of financial reporting by reflecting the current market conditions and economic realities.

The concept of fair value has evolved over time, with the recognition of the limitations of historical cost accounting. The shift towards fair value accounting has been driven by the need for more accurate and relevant information, especially in an increasingly complex and dynamic global economy.

Fair value measurements are conducted using various techniques, such as market-based approaches, income-based approaches, and cost-based approaches. These techniques aim to provide objective and reliable estimates of an asset or liability’s current market value.

The fair value hierarchy helps classify the inputs used in fair value measurements, providing users with a better understanding of the reliability and level of observability of those inputs. This promotes consistency and comparability in financial reporting.

Fair value accounting plays a critical role in financial reporting by enhancing the relevance, accuracy, and transparency of financial statements. It provides users with valuable information for decision-making, risk assessment, and evaluating an entity’s financial position.

However, fair value accounting is not without its challenges and criticisms. The subjectivity of fair value measurements, potential volatility in financial statements, and difficulties in assessing long-term value are among the concerns raised by critics. Efforts are constantly made to address these challenges and improve the reliability and comparability of fair value measurements.

Through examples across different asset classes and financial instruments, we have seen how fair value measurements are applied in practice to determine the value of various assets and liabilities.

In conclusion, fair value accounting is a cornerstone of modern financial reporting, providing users with relevant and reliable information about an entity’s financial position. It continues to evolve, with efforts to strike the right balance between capturing market dynamics and ensuring transparency and comparability. Fair value accounting remains a vital tool in assessing an entity’s financial health and making informed investment and lending decisions.